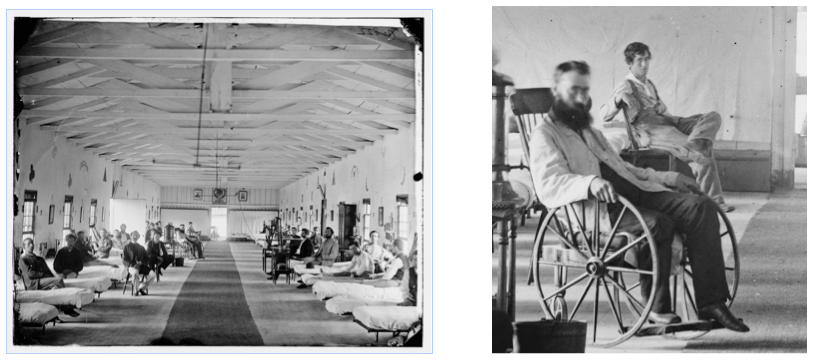

My a-ha! moment occurred late at night while sleuthing through the Online Prints & Photographs Division of the Library of Congress. I stared at a high resolution image of a glass plate negative created in 1865. The photograph depicted wounded Union soldiers in an Army hospital. I zoomed deep into the picture and focused on an emaciated young soldier sitting at the back of the room. His eyes pierced mine, and I wondered how he would react to a visit by President Lincoln.

At the time, my wife Nina and I were doing research for an Abraham Lincoln script. Nina has been a Lincoln buff since age 8, when she discovered The Abraham Lincoln Joke Book on her parents' shelf. As for me -- a tall, red-headed immigrant -- I always identified with Lincoln as a gangly outsider who succeeded without help from the establishment. The first script Nina and I wrote together was Lincoln's Hat, the story of Commander-in-Chief Lincoln leading our nation through the Civil War, told from the perspective of his hat, which doubled as a repository for Lincoln's letters, notes and other secrets. We worked on that project for two years. It was sparking interest around town when Steven Spielberg announced he was making a Lincoln movie, based on an unpublished book by Doris Kearns Goodwin and starring Tom Hanks. Lincoln's Hat died.

We picked ourselves up, and eventually made the independent film, When Do We Eat? Our Passover comedy became a cult hit and for many, an annual tradition. We never lost our desire, however, to tell Lincoln's story. Years went by and Mr. Spielberg did not make his film. No one would help us make ours because he might move forward at any moment. It didn't matter that Spielberg himself said, "The subject of Lincoln is inexhaustible." It was frustrating.

We finally opted to move forward on our own. As independent filmmakers, we would find an independent way to make a Lincoln film. Having grown as writers, we revisited Lincoln's Hat and realized we could do better. A hat is not an emotional point of view. We reopened our Lincoln books, and became fascinated by Ward Hill Lamon, a Southerner large in both size and personality. Lamon was Lincoln's faithful friend -- the only friend Lincoln brought to Washington and his closest companion during the White House years. The Secret Service did not yet exist, and after the first assassination attempt in 1861, Lamon appointed himself the president's bodyguard.

Lamon saved Lincoln repeatedly from murder and kidnap plots, while soothing the president's tormented soul with his banjo and good cheer. Lamon was not present at Ford's Theatre that fateful night in April 1865 because Lincoln had sent him on a mission to his native Virginia, but it is Lamon who redefines that tragic event in a surprising and uplifting way.

From Lamon's perspective we embarked on a new script, Saving Lincoln. As we worked, there was one question in the back of my mind at all times, "How will I tell this epic tale on a very indie budget?" I spent hundreds of hours studying photographs in the online division of the Library of Congress in order to understand the world Lincoln and Lamon occupied. One night I zoomed deep into that hospital image, and settled my cursor beside the emaciated boy at the back of the ward. And then it hit me.

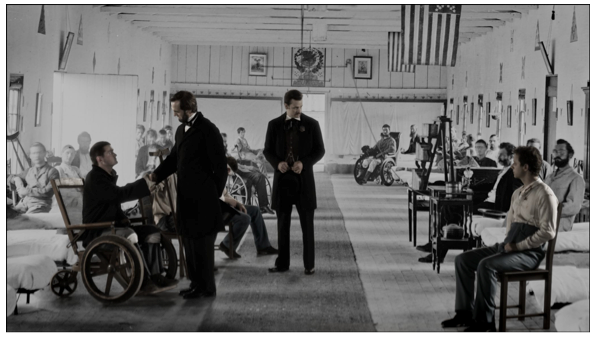

Just as I was moving my cursor through a 150-year-old image, so could I move my camera. Why recreate the Civil War world when it's already been photographed by pioneers like Mathew Brady and Alexander Gardner? I would use their photos as my sets! Most people told us me I was crazy, but a few fell in love with this visual idea, as well as the emotional approach of our script.

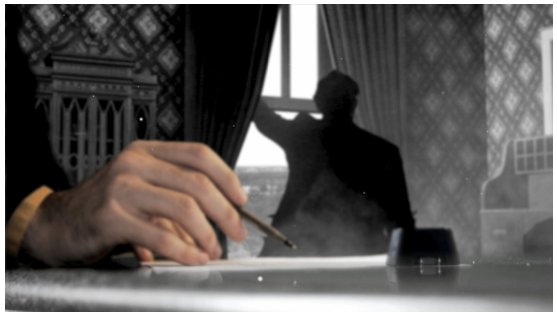

We began testing and pre-visualization, creating mock-ups of this new kind of film. One of the scenes caught my eye: a close-up of a hand writing a letter. The hand was in color, the background in black & white. I loved this hybrid look because it matched the tone of Lamon's memory piece and captured the feeling of his book, Recollections of Abraham Lincoln.

The hybrid approach also allowed us to "show our seams." At our budget, we couldn't maintain Avatar-style visual effects for every shot in the movie. Our unique approach would make it clear that we were going for something different, blending theater and film into a stylized reality. The resulting look invites the audience to complete the picture with us. I named this new cinematic style CineCollage.

As we approached the start of production, Mr. Spielberg announced that he was finally moving forward on his film, with Daniel Day-Lewis in the title role. We knew he'd be telling a similar story, but we knew he wouldn't be doing it from Lamon's point of view, and certainly not in CineCollage. We pressed on.

I cast only actors with extensive theater experience. During production, I showed them the photographs they would eventually occupy, but they had to rely on each other to stay grounded while performing in the midst of a 140-foot green screen stage. My cinematographer matched angles with his 19th century counterparts. We worked in a warehouse in downtown L.A. in August. Hundreds of our friends come down and put on heavy wool costumes to help us fill out the crowd scenes. We were a band of brothers and sisters sweltering in the heat, adding our faces to those of our photographic "extras," like that emaciated boy in the hospital ward. Saving Lincoln had truly become a film of the people.

During post-production, we collaborated with digital artists in L.A., New Orleans, Detroit, Europe and India, as well as students from the Academy of Art in San Francisco. Despite our micro-budget, hundreds of people worked on the film because the project inspired them. Toward the end, we ran a Kickstarter campaign to expand our marketing and distribution efforts. Backers stepped forward, more than 90 percent of them strangers who'd heard about the project online. They helped us double our Kickstarter funding goal. Saving Lincoln had become a film by the people.

Meanwhile, we were running a determined effort to make Saving Lincoln a film for the people. We launched a Facebook page and we post content about Lincoln, the Civil War, veterans, and historical photographs every day. People find our Facebook page and engage by liking, commenting and sharing at levels comparable to film pages with 20 times as many followers, and 1000 times more marketing dollars. We reached 50,000 followers a month before the film came out. And on our Twitter account, Ward Hill Lamon tells other stories about his colorful life, and he has thousands of followers of his own.

As we approached the end of post-production, Mr. Spielberg released Lincoln, a brilliant portrayal of the last four months of President Lincoln's life. As Lincoln fans, we relished his fine film. As filmmakers we couldn't believe our luck: Saving Lincoln would be the only feature film in decades to tell the story of Commander-in-Chief Lincoln leading the nation through the entire Civil War. Lincoln and Saving Lincoln are complementary films.

On February 11, 2013, I traveled to Springfield, Ill. for a special screening of Saving Lincoln at the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum. Nearly 300 people were in attendance -- all of them Lincoln experts and enthusiasts. The screening was part of the Abraham Lincoln Association Symposium, held annually on Lincoln's birthday. The invitation has prestige: the ALA Symposium's featured speaker three years ago was President Obama. Everyone present was highly knowledgeable about the 16th president's life and times, and they are committed to protecting his legacy. I was told this was the toughest crowd I'd ever face.

I sat in the back, anxiously wondering what the audience was thinking as the film unspooled. When it ended, the room erupted into an extended standing ovation. It was a moment Nina and I had worked toward for 12 years. It was a pinnacle moment in my life.

Dozens and dozens of people approached me to say thank you for making Saving Lincoln. When I asked what they liked about it, they mentioned both its accuracy and the new kind of film experience it offers. They were deeply moved by the story and performances, and seeing it all transpire in the original locations gives Saving Lincoln a level of authenticity they found remarkable.

Two days later, we had our Los Angeles premiere before a crowd of 600. Though many were friends and supporters, I was most gratified by the response of their guests, who didn't know what to expect. They said they were touched by the very human Lincoln presented from his closest friend's perspective, and that seeing it all unfold within the vintage photographic world was almost like experiencing a live show.

Saving Lincoln opened in limited release on February 15, and the reviews came in. Michael Medved called the film "Ingenious, original, impressive," and when he interviewed me on his radio show, he said Saving Lincoln "is an important film that must be seen." Jeffrey Lyons said, "Visually innovative and superbly acted." Kirk Honeycutt said, "Provocative and arresting." Neil Genzlinger of the NY Times praised Tom Amandes (who plays Lincoln) for his low-key approach to the Gettysburg Address, which "elevates the words." And the illustrious Harold Holzer, author/editor of 44 books on Lincoln and the Civil War, called the film "brilliant, brave, tough, incisive and entirely factual."

Perplexingly, many young critics derided the film's stylized look. They misunderstood the film's visual language, and accused it of looking slapdash. A writer for the Village Voice actually gave us a 0 out of 100. He completely missed the emotional experience everyone else is having in theaters. Our audience, however, is far more important to us. People have been coming to see the film two and three days in a row. They sit through all the credits just to extend the experience a little more. We're continually receiving thank you notes, and they tell us Saving Lincoln moves them to tears.

We are now partnering with Tugg Films to enable anyone in America to create a screening in their own town, utilizing the resources of the largest theater chains. Film is a communal experience that should be seen on a big screen. We know many people would rather see it at home, however, so we're making Saving Lincoln available simultaneously on iTunes. To give those folks the communal experience, we are setting up virtual Q&A's where they can speak with me and members of the team online.

For Nina and me, a mom-and-pop filmmaking shop, it's all a bit overwhelming and profoundly gratifying. We owe a debt to Abraham Lincoln, Ward Hill Lamon and all the boys who fought and died for the freedoms we now enjoy. We honor them by working with Operation Gratitude at all our screenings, providing audience members with postcards on which they write thank-you notes to our troops overseas. The cards accompany care packages, and when soldiers and sailors attend screenings of Saving Lincoln, they tell us how much these notes and packages mean to them.

I invite you to visit SavingLincoln.com, see our trailer and learn how you can experience Saving Lincoln for yourself. It is a uniquely American movie, made of the people, by the people and for the people.

No comments:

Post a Comment